Public Space & Ecological Knowledge

2021-07-06 • Liz Kramer

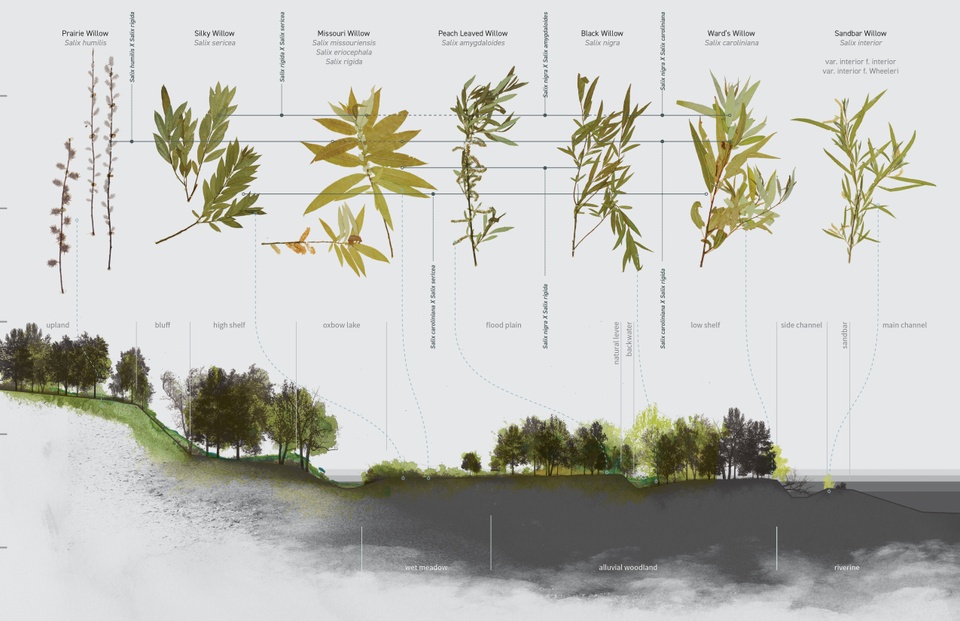

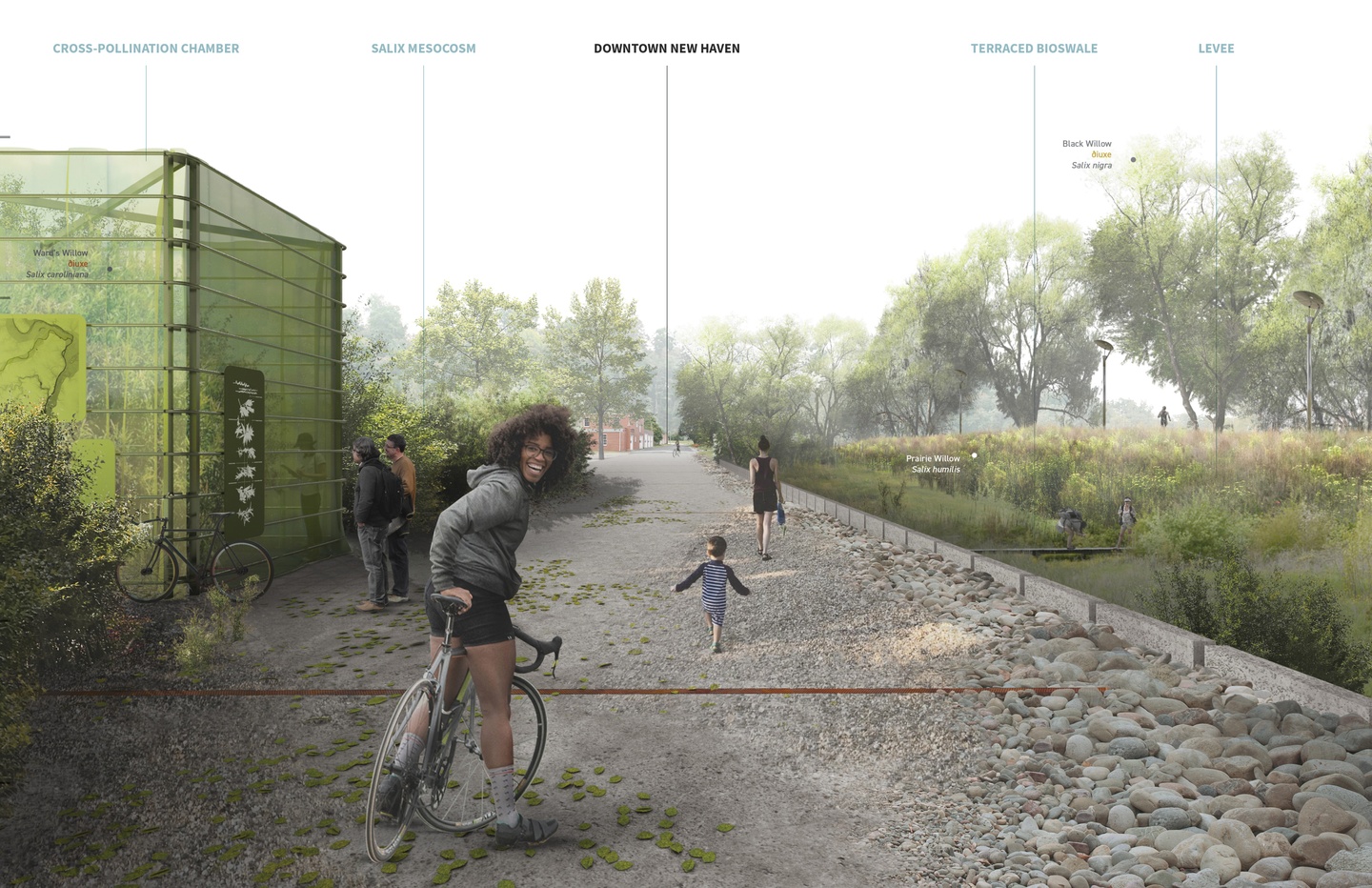

The Salix Hybridization Garden in Old New Haven operates as a performative microcosm, exemplifying interactions between wider ecological cycles and systems of production. The Salix mesocosm and prefabricated control chambers place field research within the public domain, disseminating knowledge and method to casual visitors. Integrated signage illustrates the process and aims of cross breeding various willow species. By John Whitaker.

Fall 2020 landscape architecture seminar led by lecturer Micah Stanek

In this landscape architecture seminar, students explored how public space is shaped: by design, as well as by political, social, and environmental dynamics. To understand the process and cultivation of ecological design and urbanism, students explored examples from history through the present, discussed the role of advocacy and public awareness, and speculated about how design could further engage with ecology.

“This course came out of a curiosity about the capacity of landscape architecture to promote advocacy, communicating new ecological knowledge to a larger public,” said lecturer Micah Stanek. “We looked at history, theory, and precedents. We looked at various definitions of public space.”

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the course was hybrid, with over half the students learning remotely. The first half of the semester was spent reading, touring (in person or virtually), conversing with experts, and researching as a group. During the second half of the semester, students focused on a single public space to understand how ecological ideas are studied there, and how ecological values are cultivated through design and operations. These studies investigated questions such as:

- Should ecological agendas be a matter of science and governance, or does ecological urbanism require democratic participation?

- Can designed spaces communicate ecological ideas to a larger public?

- Could design be instrumental in the discovery of new ecological ideas?

“From this course, I learned how designers can build a bridge between the public and ecological knowledge,” said student Danni Hu. “Developing my project allowed me to focus on transforming ecological knowledge into a simple and straightforward installation design to attract people’s attention to ecology visually.”

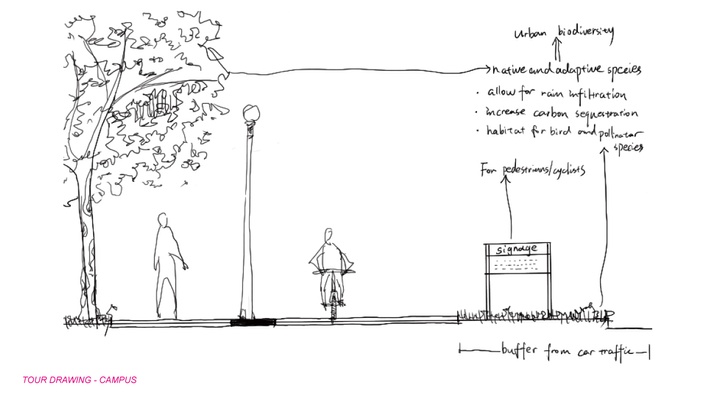

One highlight of the semester was participating in hybrid tours through Forest Park and the Danforth Campus. Students looked closely at these spaces, examining the various ways different publics read ecological design. The class located interpretive devices and pondered ways that people might tune in to the ecological ideas in the world around them.

Toward the end of the semester, students created a speculative design that set the stage for a full-scale project. Student gravitated toward creating signs or markers that interpret abstract or concrete ecological processes in Forest Park or on the Danforth Campus.

“We initially hoped to make physical, real interventions, but this was difficult given the context of COVID-19,” said Stanek. “In the meantime, the students learned more about ecological processes and public spaces by speculating about how they might be marked and interpreted.”

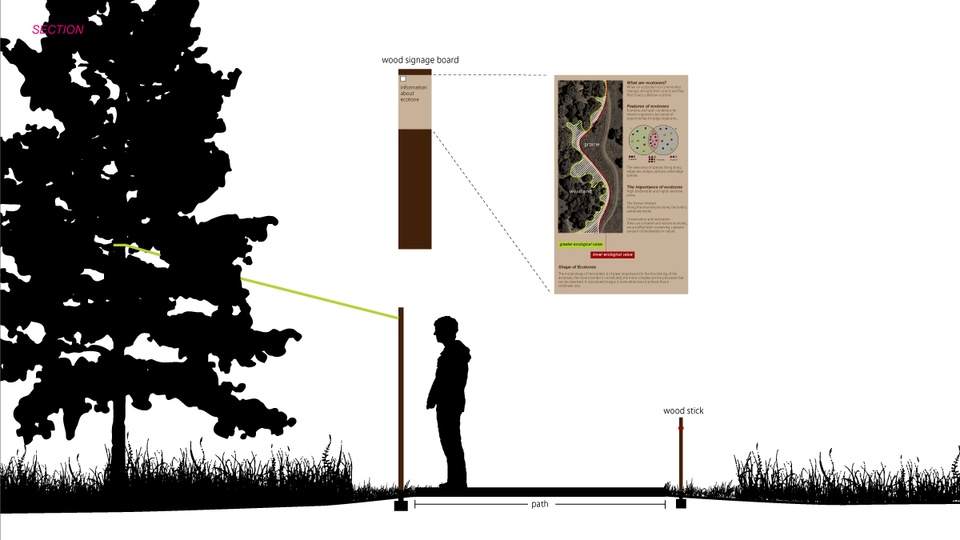

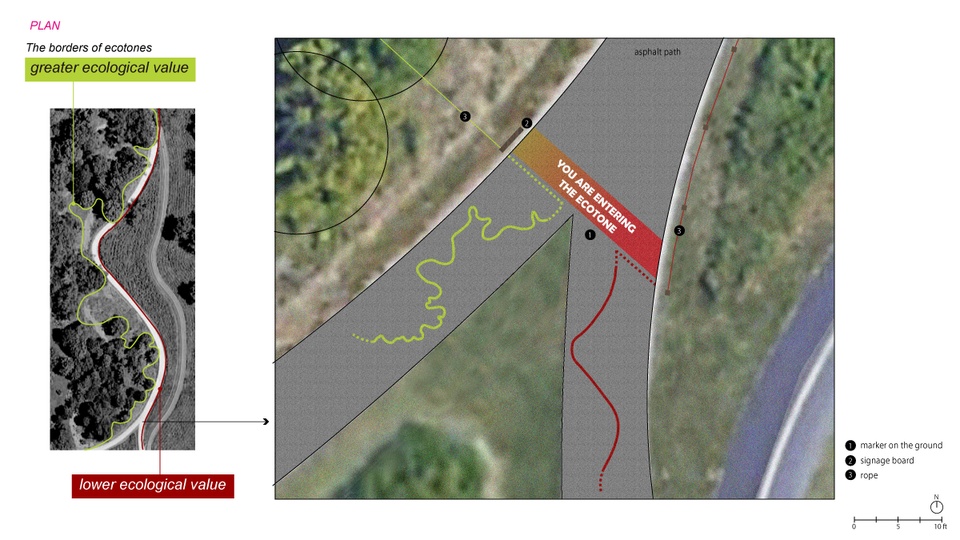

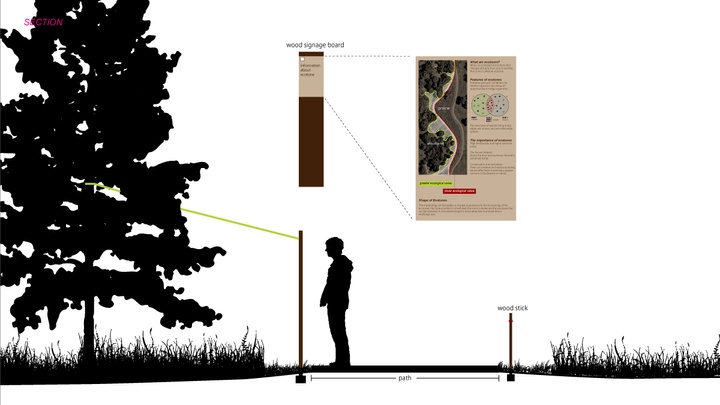

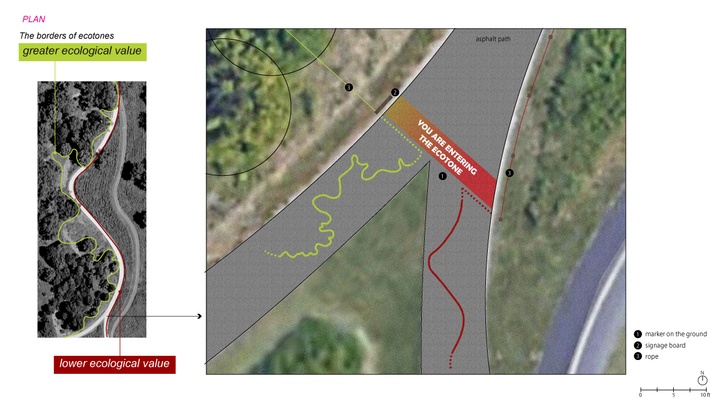

Student projects explored a range of ideas. For example, Hu’s project Entering the Ecotone aims to disseminate knowledge about ecotones in public space. Ecotones are the zones where ecosystems abruptly change from one system to another and are essential for the conservation of biodiversity. The intervention proposes communication methods such as painting on the path and installing wood signage to convey the transition to the public. The intervention also challenges the public to see the value that the shape of an ecotone has in promoting biodiversity. Organic and convoluted margins are more attractive to animals than linear margins, so Hu showed the differences with rope installations of different colors.

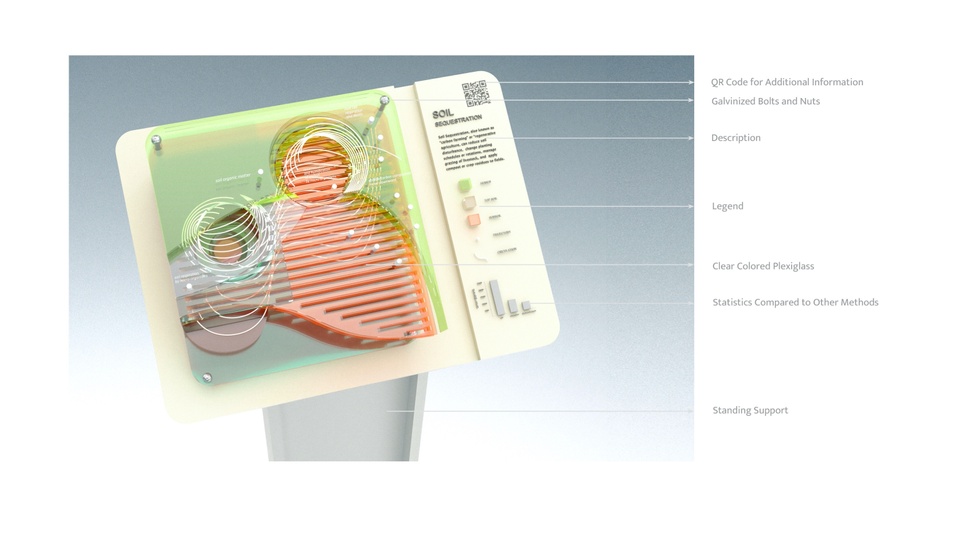

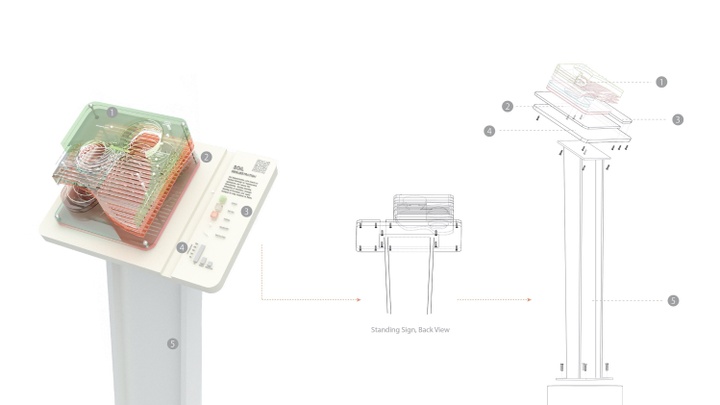

Chuchu Qi’s project focused on the visualization of carbon sequestration strategies in Forest Park, choosing a site near the Norman K. Probstein Golf Course and the Kennedy Forest. Through Qi’s explorations of different carbon storage methods, including soil, rock, concrete, biochar, peatlands, ocean, forest, costal vegetation, and industry, the project showed how carbon sequestration strategies vary in different landforms. The visualization allows the audience to learn about sequestration strategies and how they’re used.

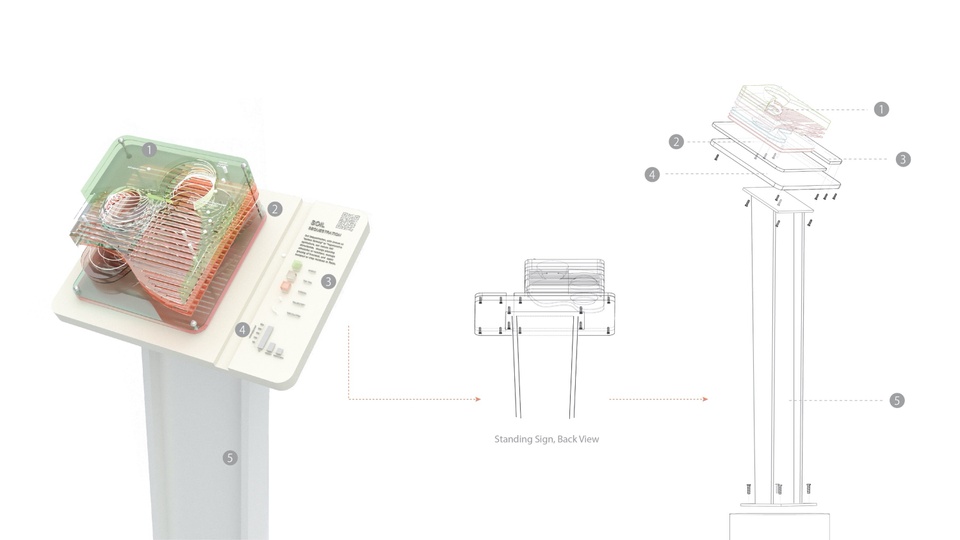

“This was my first class for the landscape architecture minor,” said Qi. “I started the project with the index diagram that demonstrates the different carbon storage methods. The design strategies I used in the matrix inspired the final design of the standing sign with the different transparency of the colored plexiglass and the arrangement of the layers to represent the existing carbon sequestration process in Forest Park. The additional information on the side of the layered plexiglass also provides the audience with the general description text, QR code, and a histogram that offers the comparison of the carbon sequestration strategies on different landforms.”

Boyan Zhang’s project Wild Garden proposes the creation of a small garden along the common chain-link fence seen across urban areas. Within the garden, spontaneous plants that are seen throughout the urban areas are planted.

“These species are ecologically resistant to different special or even negative growth environments,” said Zhang. “When the plants are left to grow freely, these negative environments are created in the garden. In this way, I have created a micro, wild ecosystem with natural ecological diversity and also a wild-like public space for visitors.”

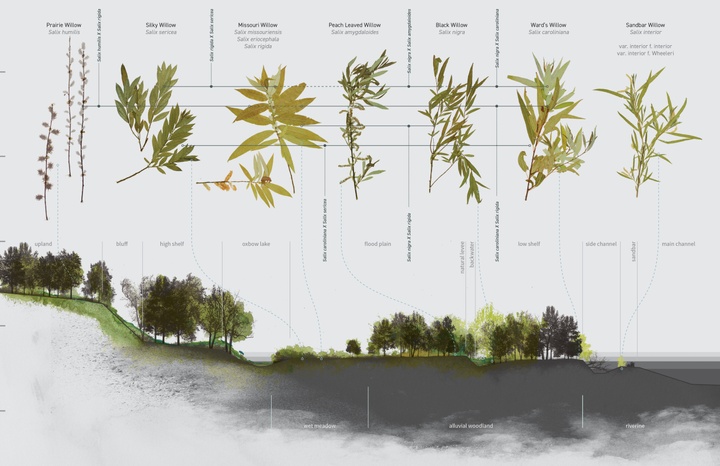

John Whitaker’s project New Haven Hybridization Garden is a proposal for a more expansive cooperative between the residents of New Haven and Treloar, Missouri, working within the natural systems of the lower Missouri River Valley. The New Haven Hybridization Garden creates sites of experimentation within the public spaces of a fading river community, offering a path toward revitalization and engagement of the region’s economic and environmental systems. The proposal utilizes the rapid growth patterns and regenerative properties of willow. When harvested, willow root systems remain intact, retaining alluvial soil, sequestering carbon, and storing energy for rapid regrowth. The project proposes evolution and advancement through research, data collection, and knowledge production.