Beverly Semmes

Golden G

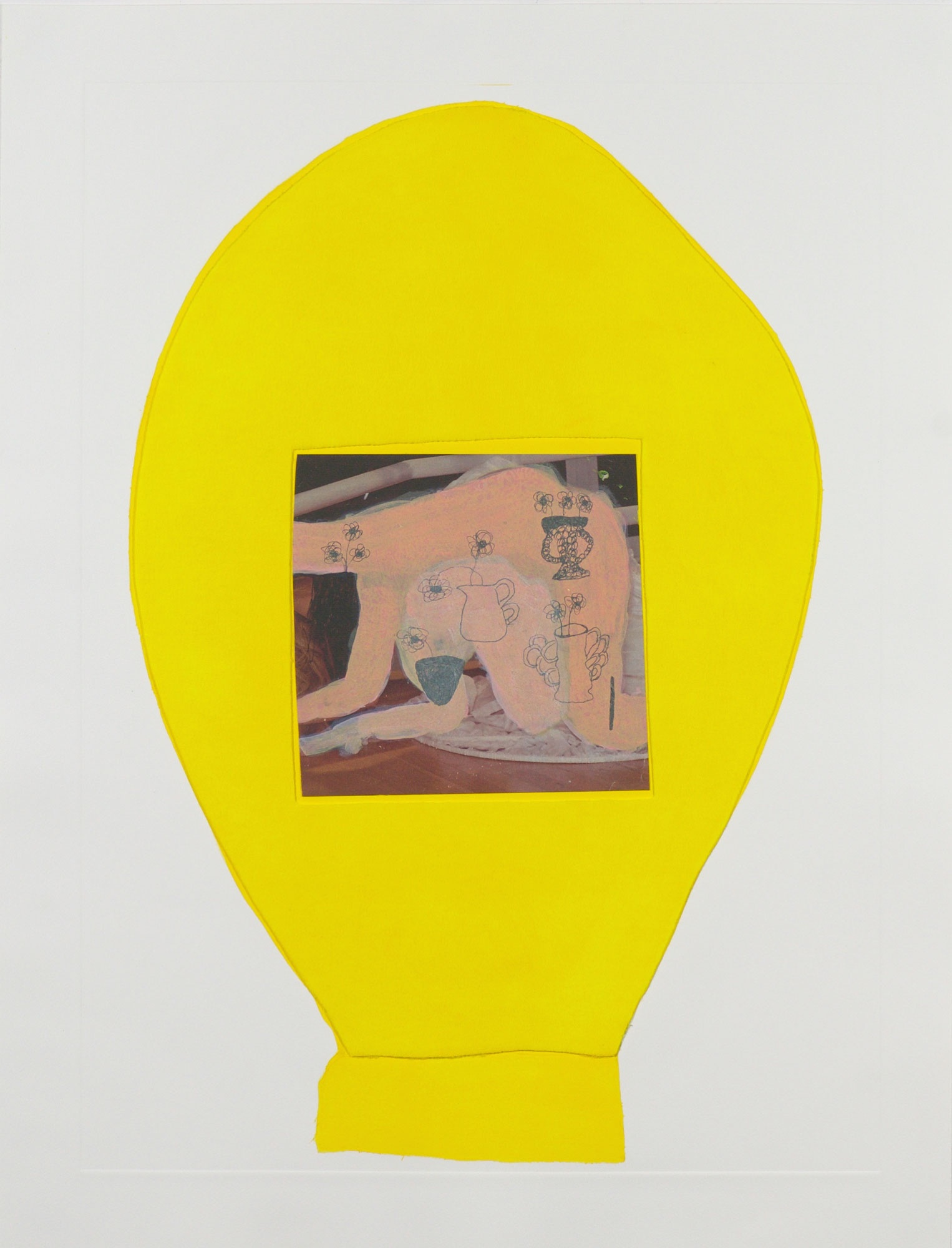

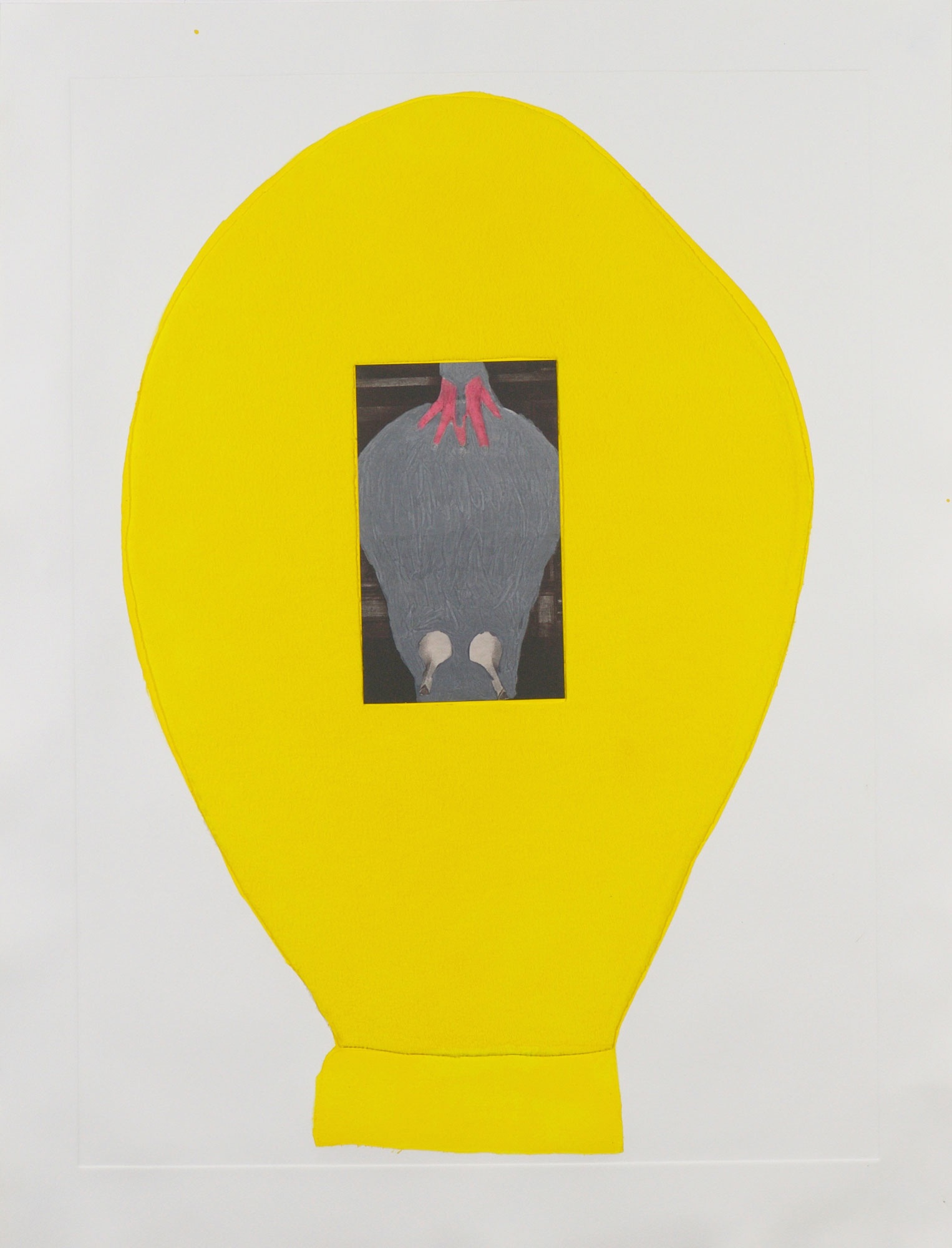

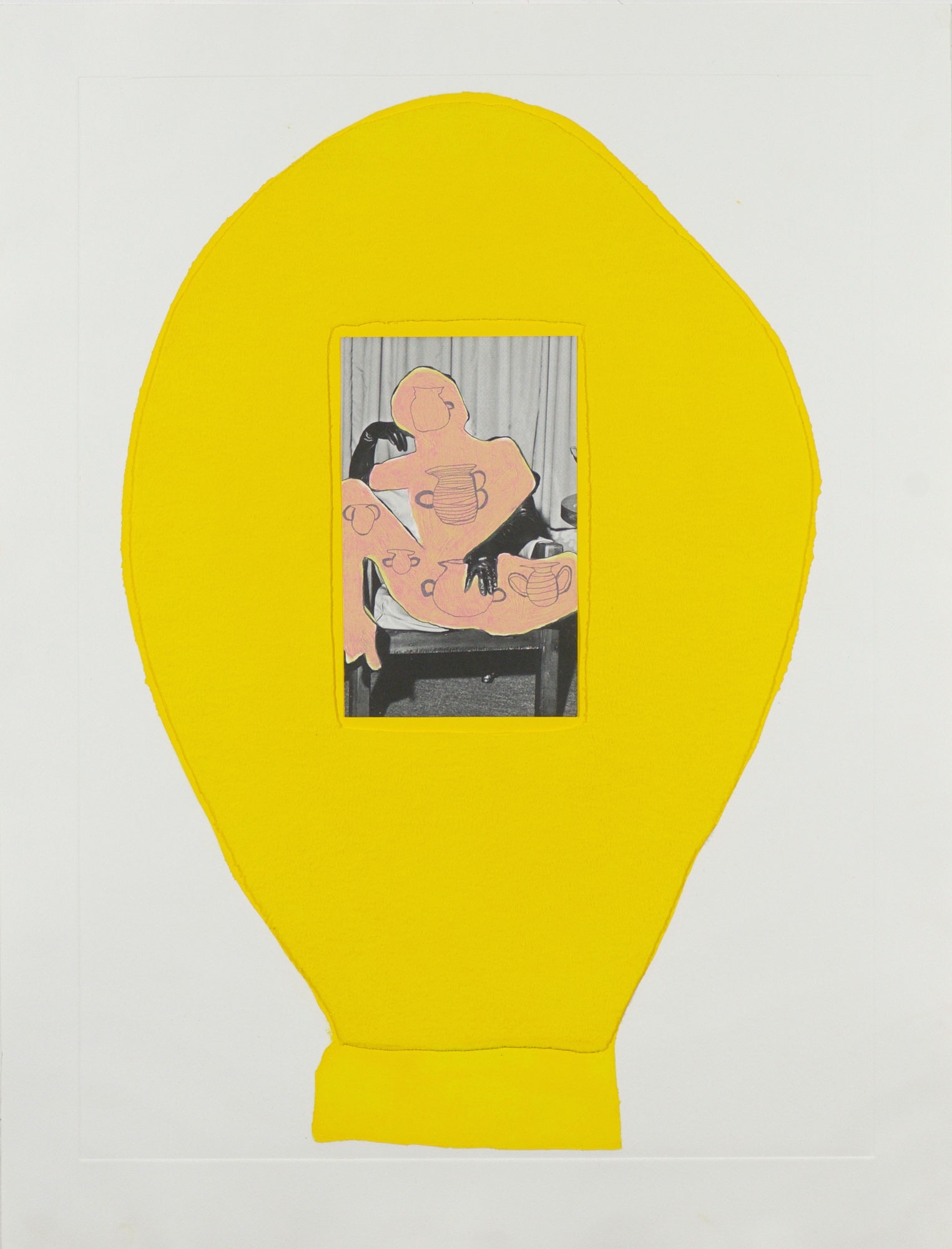

Beverly Semmes’ Golden G: Flowers / Heels / Curtains is a series of three editions that combine inkjet prints layered with intaglio and set into frames of printed acrylic fleece. The editions connect Semmes’ ongoing Feminist Responsibility Project (FRP) to her 2016 exhibition at Susan Inglett Gallery, which debuted the ghost shapes (the “G” stands for ghost).

PROOF essay by Stephanie Ellis Schlaifer, author, poet, and artist

Beverly Semmes’ Golden G: Flowers / Heels /Curtains is a series of three editions that combine inkjet prints layered with intaglio and set into frames of printed acrylic fleece. The editions connect Semmes’ ongoing Feminist Responsibility Project (FRP) series to her 2016 exhibition at Susan Inglett Gallery, which debuted the ghost shapes (the “G” stands for ghost) that frame the Island Press redactions. Much of Semmes’ work involves editing and erasure. Symbolic repositories for femininity—dresses, vessels, and decadent fabrics—all become platforms for manipulation and metamorphosis.

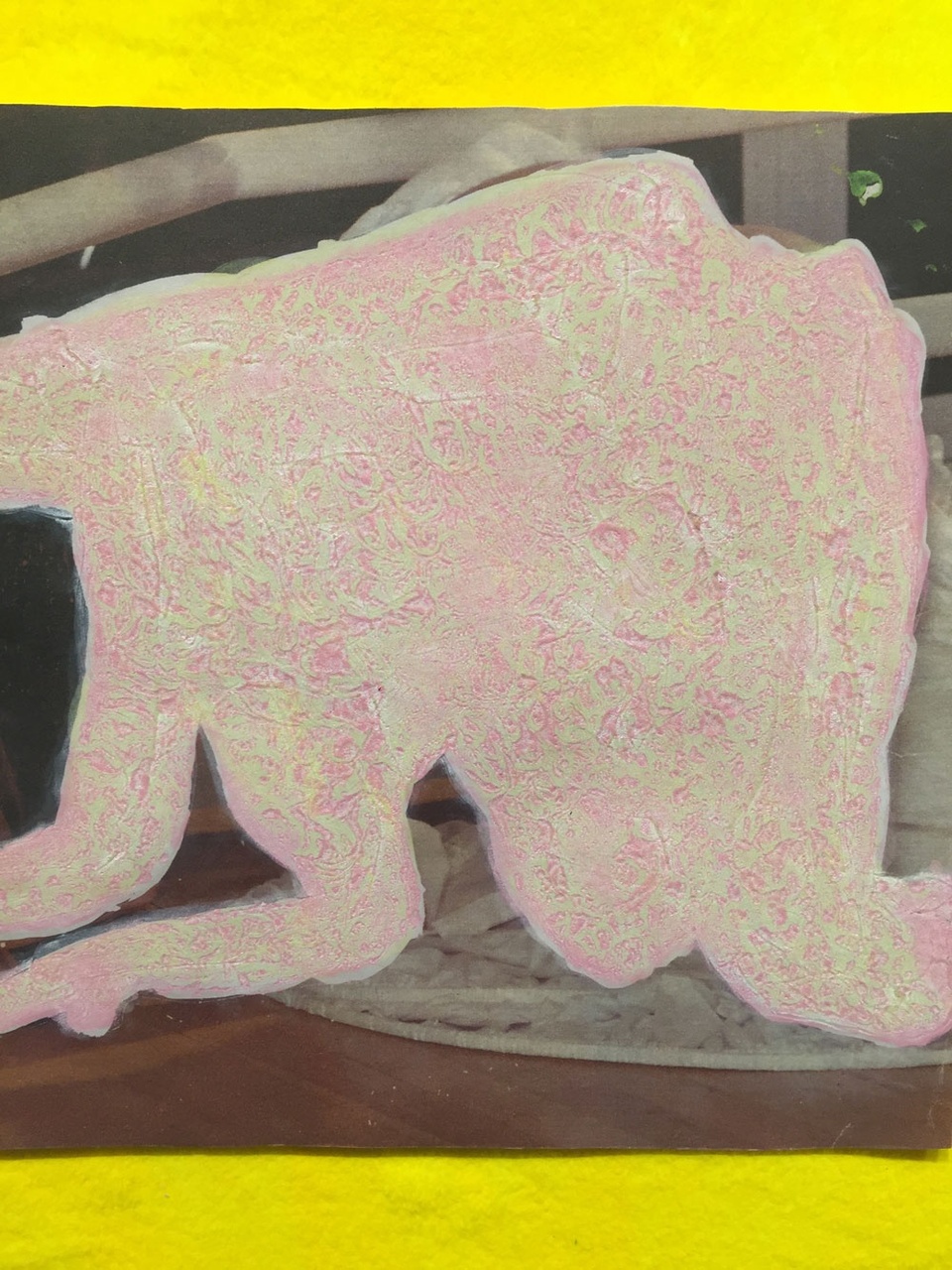

In the FRP, pornographic magazine images are painted over, printed on, and markered out with deliberate crudeness—as a child might deface a picture of herself. In the Inglett show, Semmes pairs these redactions with sculptural work in fabric, clay, and crystal, often playing with surrealist humor in a nod to Oppenheim’s fur-covered teacup. Some sculptures confront the viewer with nightmarish excess. A velvet party dress is alarmingly elongated. The arms—more self-extruded than stretched—are distressingly tubed. The distortion reads like a body’s overreaction to stress: what should be self-protective becomes destructive.

Golden G brings the redactions into relief. The dimensional frames were created by affixing cut fleece shapes to the paper and printing on top of them. They recall the amorphous, ghostly bodices of the Inglett show, and become much like inverted vessels—an insistent motif in Semmes’ work. Semmes applies her sculptural forms to the Golden Gs in a kind of self-quotation. On these marked-out bodies, the vessels appear. They are never of the bodies, but rather stuck on—concealment and spotlight at once.

Semmes’ palette is narrow and accusatory—colors so garish you feel interrogated by their brightness. Zesty citron becomes sourly fluorescent. Strawberry and gold pair like frosting and mustard. The limited palette creates an argument of color. In the Golden Gs, the bulbous frame is doggedly yellow. In this harsh beam, flesh tones flatten to beige. The inking over the flesh with flesh-tones emphasizes the discomfort with the image and what’s mirrored in it—one’s own skin.

Semmes isn’t interested in heroic reframings—these are desperate, hasty cover-ups. They’re not meant to liberate anything. The models never escape the lewdness of their poses. No matter how flat, how smooth, how simplified, the crotch is always a crotch. In some cases, the altered image is more objectifying than the original. The women’s face and genitals reduced to nothing but a horrifying, dark geometry. By someone desperate to blot them out. The images seem created not by Semmes at all but by a persona—an off-screen redactor—someone discomfited but obsessed. She takes up an invented mantle—a fetishized chastity. Semmes turns these objectified beauties not into modest mice but beast Jesuses. Her marks are desperate evidence of a consuming process—of trying to unsee.